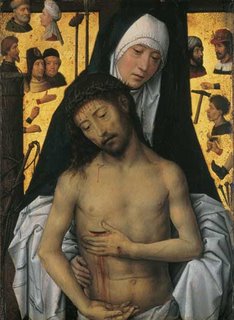

The Man of Sorrows in the Arms of the Virgin, by Hans Memling, fifteenth century.

The Man of Sorrows in the Arms of the Virgin, by Hans Memling, fifteenth century.Yesterday I was teaching a section on women mystics of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and I decided to read a passage on Angela of Foligno from Caroline Walker Bynum's fascinating book Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. It is true that I picked some particularly provocative images, but I wanted my students to get a sense of how intense and intensely physical these ideas were:

Angela repeatedly referred to Christ as "our food" and "our table," and in a vision saw him put the friars of Foligno, her "sons" into his side, whence they emerged with lips rosy from drinking blood. On another occasion Christ appeared to her all bleeding and gave his wound to suck...The students were shocked, but in the context of the class, most of them understood what I was trying to demonstrate: that these visions were a way for women, whose Eucharistic devotion was always mediated by male clergy, to experience the truths of the Eucharist in a startling literal and physical way. The physicality that we find so disturbing made sense in the context of their particular spirituality, and in the general spirituality of the time.

One student, however, was horrified and refused to see the vision as anything but pathological. She said that it was the result of women being cloistered to the point of becoming morbid, and that no woman who had lived in the world would have a vision of this type (Angela was a wife and mother before becoming a third order Franciscan, and was never cloistered). Other students argued with her that in the context of Eucharistic piety, the visions, although intense, made sense. The student, however, insisted that it was unhealthy, and eventually she extended her feelings to the general idea of the Eucharist. It was based on bloody sacrifice, she felt, and society needed to get beyond it to be healthy. The idea of eating Christ's body and drinking his blood was nothing short of vampiric, and came from ancient pagan and barbarian roots.

I hope I have presented her arguments faithfully. I don't agree with her, but I think those of us who do believe in the Eucharist should think about both Angelina's intense physical literalism and my student's reaction against it. This is especially true as Holy Week approaches and we commemorate the Passion of Christ. It is very easy to forget the import of what we are doing. God made man and tortured to death. The intermixing of God's flesh and ours through the intimate act of eating (whether you believe this is done literally or symbolically, it is still an extremely provocative idea).

Do we need sacrifice? Do we need blood? I think that it would be very naive to see this world, with all its violence and brutality, as a world that does not need to be healed. My student would say that the very idea of sacrifice perpetuates brutality. What if, however, everything could be reversed? If God, instead of demanding a lamb for bloody sacrifice, was that lamb? If God suffered in the flesh -- the warm, bloody, flesh -- what is to be suffered in this world? What does the cross mean? I think the profundity of all this demands no less than the most powerful, physical, and intimate of religious experience.

Angus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

3 comments:

Not everyone buys completely the atonement spin on Jesus' death - that he is a sacrifical lamb, so to speak. There's an interesting article about that at American Catholic about that - here

btw, have you ever read Stranger in a Strange Land? At the very end, the main character's followers eat him :-)

Crystal-

I guess with all the blood and whatnot, I was sounding the atonement note a bit more that I had wanted to. Thanks for the artcile -- as usual, I was more familiar with the medieval stuff (Duns Scotus) then the modern. I've read some Rahner, but not on this subject.

I do feel that an Anselmian economy of atonement (as I understand it) is problematic -- God having to atone to God with God. I would also agree that the center of Christ's salvation is the Incarnation, for the reasons stated in the article, and that the Crucifixion only makes sense within the context of the Resurrection. Still, I don't want to completely toss away the idea of sacrifice for a couple of reasons: 1) the liturgy is replete with the idea (the angus Dei, the Eucharistic canon), and 2) also because Christ fulfils his connection with us through his human flesh at the moment of suffering. There was a German film I saw last year called "The Ninth Day," and what moved me most about it was a detail incidental to the storyline. In one scene, in a Nazi Concentration camp where Catholic priests are kept, there is a a shot with, in the background, a priest who had been crucified by the Nazis. Seeing him hanging there against gray mud and barbed wire, it made me sense how brutal, dehumanizing, and lonely a death like that must have been. At that moment, I felt more then ever how amazing the death of Christ was, how he made common cause with those who suffered most and were most despised. That is a sacrifice, though not according to any economy of atonement. I think Holy Week is about understanding both the infinite sadness of that sacrifice as well as the infinite joy of the Resurrection. The reversal that I talked about in the post doesn't pay for sin, it heals the world by example and by love.

I do think Jesus made a sacrifice of his life for us ... this is just my personal theory and I don't know how close to true it might be, but I think he wanted to reconcile us with God and while doing that, he made enemies. He continued, even though he knew it would eventually get him killed. Perhaps he felt his death would put the stamp of authenticity on his teachings.

I'm reading in the retreat about Jesus praying in the garden, and he seems very disturbed ... imagine him growing up in an occupied land, seeing people crucified all his life ... he must have known just what to expect. I think it was CS Lewis who said something like being brave was being scared, but doing the scary thing anyway because it was right ... that was Jesus, it seems to me.

Post a Comment