The Arca Santa in the cathedral of Oviedo, Asturias, Spain.

The Arca Santa in the cathedral of Oviedo, Asturias, Spain.I have been neck deep in charters for the past two weeks or so, typing entries into my database

magna cum furia. I feel like I have been making progress, but my blogging has suffered. Oh well.

I have decided that a chapter or at least part of a chapter of my dissertation will be on forged charters. They are, content-wise, some of the most interesting documents I have studied. I will be presenting a paper at the Medieval Conference at Kalamazoo next May on one of them, but there are several that are just... just...

...cool.

Especially one that purports to be a donation from King Alfonso VI to the cathedral church of

Oviedo in 1075. It may be based on a real document that is now lost, but this charter is probably one of the many forgeries created under Bishop Pelayo of Oviedo in the early twelfth century. The best part of it is its long narrative telling how the Arca Santa (Holy Ark) was found and opened in the 1030's by then-Bishop Pontius. It emitted a light so brilliant that it blinded the bystanders. It was then re-opened in 1075 in the presence of the king, and there was a great treasure of relics (I did a quick translation from the original Latin). There were relics...

... of the Wood of the Lord, of the Blood of the Lord, of the bread of the Lord, that is, from his Last Supper, of the tomb of the Lord, of the holy earth where the Lord stood, of the dress of St Mary and of the milk of the same virgen and mother of the Lord, of the robe of the Lord that was divided up and of his shroud, relics of St Peter the apostle, St Thomas, Bartholomew the apostle, of the bones of the prophets, of saints Justus and Pastor, Adrian and Natalia, Mama, Julia, Verissimus and Maximus, Germanus, Baudulus, Pantaleon, Cyprian, Eulalia, Sebastian, Cucufatus, from the robe of St Sulpicius, St Agatha, Emeterius and Celedonius, St John the Baptist, St Romanus, St Stephen the Protomartyr, St Fructuosus, Augurius and Eulogius, St Victor, St Lawrence, saints Justa and Rufina, saints Severandus and Germanus, St Liberius, saints Maxima and Julia, Cosme and Damian, Sergius and Bacchus, St James the brother of the Lord, St Stephen the pope, St Christopher, St John the apostle, the robe of St Tirsus, St Julianus, St Felix, St Andrew, St Peter the excorcist, St Eugenia, St Martin, saints Facundus and Primitivus, St Vicent the levite, St Faustus, St John, St Paul the apostle, St Agnus, saints Relix, Simplicius, Faustinus and Beatrix, St Petronila, St Eulalia of Barcelona, of the ashes of saints Emilianus the deacon and Jerimiah the martyr, St Roger, St Servant of God the martyr, St Pomposa, Anania, Azaria and Misaele, St Sportelius and St Juliana, and many others the number of which only the knowledge of God can touch...

The Wood of the Lord is, of course, the cross. It is interesting how many relics of Jesus and Mary there are -- most relics are from a saint's body, but the bodies of Jesus and his mother are in heaven. So the relics are either contact relics -- clothes or other objects that have touched the holy bodies -- or things such as blood or milk that are produced by the body. Other relics of Christ get even stranger -- there was talk in the Middle Ages about relics of Jesus's baby teeth and even his foreskin.

Most of the relics are bones. This is quite a collection, although I wouldn't trust Pelayo too much. At any rate, many relics are just mere

slivers, so maybe there were a lot of good slivers in the Arca Santa.

Our typical reaction as moderns to relics -- even as modern Christians -- is that they disturbing, morbid, even sick. Keeping body parts on display and venerating them! I suggest we open our minds. Medieval people were more honest with themselves about death and less separated from their own bodies than we are. We keep death at a distance, send our old off to homes, pursue youth with all our money and all our time. Good Cartesians that we are, we think of our bodies as something we live in, not as something we are. People in the Middle Ages knew death was as real and as present as life, and as natural. Their dead were close to them and memory of the dead was intensely important. Their bodies were part of their selves, bodies that would resurrect on the last day. A body part of a dead saint was an actual physical object you could touch that you knew would one day be in paradise. Having that relic in your church did not mean that you had the cast-off shell, the shuffled-off mortal coil of the saint, you actually had part of the saint him/herself with you, and he or she would protect you and stand by you.

Is it sick and morbid not to forget the dead, not to be amazed at the physical? Perhaps we can learn from attitudes that appear distasteful when we don't understand them.

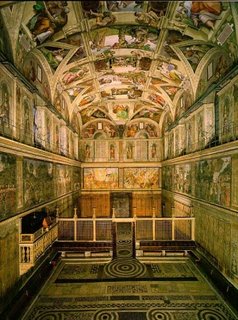

Leon, cathedral. Photo by Trepanatus.

Leon, cathedral. Photo by Trepanatus.